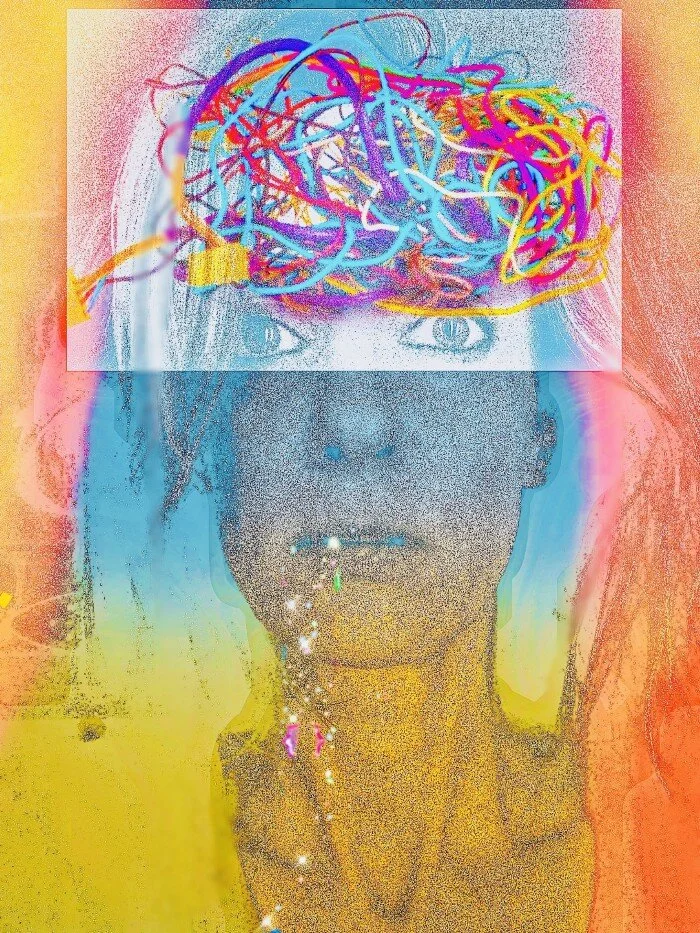

CHEERS!

HERE’S TO YOUR DIAGNOSIS!

Getting told at the ripe age of forty that I had Parkinson’s Disease kind of sucked, for reasons I hopefully don’t need to explain. You get a diagnosis like this and you can expect to drag yourself and possibly whoever is closest to you through a massive grief process, not to mention the revolving door of crises related to medical care if (when) you become incapable of holding down a conventional job. Sigh. It’s a lot to process. (Sigh again!) It’s also not going to go away like the flu, go into remission like cancer, or be potentially managed to the point of functional nonexistence with lifestyle changes, like celiac disease or diabetes. A Parkinson’s diagnosis is permanently life-changing, period.

But among all the other complex feelings that we must deal with, there’s one common reaction that doesn’t get talked about very much.

RELIEF!

When I look back, I had observable symptoms of Parkinson’s by the time I was 35. I’d assumed my stiffness and tremor were due to the chaos and stress of raising young children in one of the most expensive cities.

Who thinks “Parkinson’s” when they’re in their thirties? Probably not you, definitely not me and definitely not most people’s doctors. The American medical establishment has a legendary addiction to statistics and broad generalizations: if something is statistically unlikely, you will be shut down for bringing it up. You will be patronized. You will be told it’s in your head. (Which it is. It’s in your brain, which is contained by your head. (A special shout out goes to the first “neurologist” I visited for failing so spectacularly at doing his job.)

If you are a woman, the length of time you can expect your symptoms to be dismissed is roughly eleventeen times what a man will experience, based on my sophisticated statistical modeling. Basically, you’ll know something is wrong with you. But you won’t be able to prove it. And you’ll spend years questioning your sanity because the guy in the white coat smiles and nods and suggests you need Prozac, or birth control pills to regulate your hormonal mood problem. Your PCP is a woman? You’d think that would obviate the patronizing and dismissiveness but it doesn’t. Your female doc got the exact same master class in “ignoring what patients are actually saying to you” that her male med school colleagues did. Indeed, she might have outperformed her male colleagues in this area.

On it goes. For years. Your body starts behaving more and more like it has its own agenda, but it comes and goes, is hard to pin down, hard to describe; it could even realistically be your imagination. Maybe that doctor was right and you’re depressed and it’s just manifesting as random pain, random confusion, random balance problems, randomly shrinking handwriting, attention span, sleep hours, and muscle mass. They agree to “do some labs.” Nothing suspicious turns up. Lather, rinse, repeat. God forbid you follow the white rabbit to the eternal hellhole that is “googling your symptoms,” which will convince you you’re dying while simultaneously convincing you that the doc was spot on and that you’re experiencing a delusion!

Unless you are quite elderly when you start experiencing symptoms, the odds are overwhelming that no one will take Parkinson’s Disease seriously as a diagnosis and you will be bounced around the medical system like an awkward pinball, possibly for many years. The disease progresses in a passive-aggressive snit. The doctor runs out of ways to tell you you’re imagining it. Imaging tests like brain ultrasounds, MRIs, and CT scans are relatively useless in confirming a PD diagnosis; it’s essentially a diagnosis based on self-reporting and observation of symptoms by a neurologist. It can take years just to get past the PCP who doesn’t believe you need a referral to a neurologist because you’re too young for Parkinson’s so you must be a hypochondriac or a drug seeker or have a panic disorder. To add dry, tindery underbrush to this forest fire, both the disease itself and the inability to understand what the hell you have will cause mood disorders eventually, so you have to contend with the ugly fact that you probably are also anxious and depressed.

This is why many of us receive the words “You appear to have Young Onset Parkinson’s Disease” with an overwhelming feeling of relief. Giving the monster a name is probably the only thing that can put it in perspective and point you in a direction to pursue treatment and optimize your quality of life. When you have no idea what’s happening to you, you’re helpless. Once you have a diagnosis, you can make meaningful choices on your own behalf and your doctor might even finally admit that it isn’t “in your head” so much as in your brain. It’s a serious bummer when it sinks in. You’ll cry. You’ll go into a rage. You’ll experience absolute terror.

At some point you’ll peel yourself off the floor and realize that at least now you have something to work with: a name. An explanation. A context. A starting point for redefining your life, your relationships, yourself. You get back a sense of agency (at least sometimes) and feel enabled to advocate for yourself in the outside world. I’ll meet you there, with streamers and a karaoke machine and a dopamine agonist. We can sing THIS AWESOME TUNE , and shake the night away!